Saturday, December 31, 2011

Random thoughts after a week and a half

2) The crew on this boat seem to be the least friendly of the three overall, although on every cruise there seems to be at least a few crew members that for some reason don't like the scientists (specifically the male scientists). They always seem to be friendly to the female scientists though, which I guess is not surprising since the ratio of men to women is usually around 10:1. The crew has sort of made the library their "territory" and the one time I went in there a few nights ago I felt like I was interrupting a private party and got some dirty looks from a few people in there. With that said, there are plenty of nice people in the crew that I've chatted with a bit, and the marine techs (the people who work directly with the scientists) are nice, as they usually are. I don't want to make it seem like the crew is mean or anything, I just feel like there are a few of them that are resentful of us for some reason and just aren't very friendly (Sam (another UH grad student) has noticed the same thing, so it's not just me). We'll see if my opinion changes as the cruise goes on, it could just take them a little while to warm up to us.

3) We have had issues with just about every piece of scientific equipment so far; nothing that is preventing us from getting the data we want, but everything has not gone smoothly. The deep-towed sonar has been having problems, mostly on the starboard side, since the beginning. The sidescan returns were very weak for the first survey and the bathymetry data pretty much looked like crap, maybe a third of the starboard swath was actually usable data. After the first survey area, they found a short in the starboard electronics and fixed it, so it has improved for the beginning of the second survey area, but apparently it is still not quite as good as it should be. One of the MAPR's, which is an instrument that we attach to the sonar tow cable to detect the signature of a hydrothermal plume in the water column, crapped out on us as well, but there are extras so it wasn't a big deal. The dredging also has not gone as well as hoped. They have had a few good dredge hauls with a fair number of rocks, but some of the dredges have come up empty and many have been very small. They were actually picking little tiny bits of rock off of the deck with tweezers on a few dredges because they needed to get every last bit of rock that they could. On the last cruise, we would have just swept that stuff overboard, we always got at least a full 5 gallon bucket worth of rocks, and sometimes as much as 8 full buckets. The variety of the rocks in the first survey area was also not very exciting. All of the samples were pretty much the same stuff: all basalt (the typical lava composition erupted at most spreading centers), with no visible crystals, not much variation in texture, and very few vesicles (gas bubbles). It definitely makes me appreciate both the quantity and variety of rocks that we got on the last cruise. However, we are now mapping the forearc rifts and will be dredging these after the mapping is done, so we will almost certainly see a greater variety of rocks along these structures than the first survey area which was along the backarc spreading center.

4) Two nights ago was the best stargazing I've seen on any of the cruises so far. There were a ton of stars and I could actually see the Milky Way, which I have not seen on either of the other boats. I spent almost an hour laying out on the hammock, listening to some tunes, and looking at the stars, it was really nice. It helps that the fore deck of this ship is darker than the other two so there is less light to interfere, plus there was no moon. However, I still don't feel like it was better than the stars I've seen camping out in the Sierras or Northern California, you just can't get complete darkness because they always have to have at least some lights on on the ship.

5) We did have a mini New Year's Eve celebration last night in the main lab. The scientists from U. Rhode Island and UT Dallas bought a blue godzilla pinata in Guam and we had some fun taking turns hitting it, so it was nice to do something a little festive. Otherwise, New Year's pretty much has felt like any other day on the cruise. In case I hadn't mentioned this already, alcohol is no longer allowed on American research vessels, so there was no champagne to start the new year.

Sunday, December 25, 2011

The Instruments

A small (I couldn't get a larger version without signing in) schematic image showing the deep-towed sidescan sonar setup. You can see how the beams are oriented, the blank spot directly below the instrument, and the strong reflections/shadows on either side of the volcanoes. I'll post an actual image of what the data looks like later.

A small (I couldn't get a larger version without signing in) schematic image showing the deep-towed sidescan sonar setup. You can see how the beams are oriented, the blank spot directly below the instrument, and the strong reflections/shadows on either side of the volcanoes. I'll post an actual image of what the data looks like later.My job on this cruise is to do some of the initial processing (called "bottom detect editing") of this data as it is collected. I work a 9 hour shift from 6 pm-3 am. Fernando's (my advisor) other student, Regan, is doing another 9 hour shift from 3 am to noon, and one of the employees of the group that owns and operates the instrument (Hawaii Mapping and Research Group (HMRG)) is covering the noon to 6 pm shift. It is somewhat difficult to explain what exactly I'll be doing and I'm not fully comfortable with all of the technical details of how these instruments work, but basically I'm making sure that the instrument knows where the real bottom is. Because we're dealing with sound waves and they aren't as precise as something like a laser, there are a lot of echoes and reflections that confuse the instrument. The instrument has an array of transducers (the things that emit and detect the sound waves) on either side, roughly oriented 45 degrees from vertical. Sometimes the sound reflects off something in the water column that is not actually the seafloor, and sometimes the sound waves from one side of the instrument are picked up on the other side of the instrument. This can make the instrument confused as to where the real bottom is on a particular side. So I look at the raw data right after it's collected and try to find the reflection that represents the "true" bottom. However, because we don't actually know definitively where the bottom is, it can be very ambiguous sometimes, especially when the topography is complex and/or different on either side of the instrument. The guy who is in charge of HMRG calls it a "dark art" rather than a science, and this is an apt description. The basic idea is not to be 100% precise on getting the actual bottom, because you can't, but rather to make the image more believable and easier to interpret and to eliminate the obvious errors. Sometimes it is very clear where the true bottom is, sometimes it is not clear at all. So far, it has been going pretty well, there have definitely been some ambiguous swaths, but I'm getting more and more comfortable and efficient with the process. Unfortunately, the first survey area is along the spreading center, which is the simplest of the three survey areas, so it will likely be more difficult for the other two areas.

The other major part of the mission is sampling the volcanic features that we see in the sonar data. I will not be involved in this part of the operation, beyond checking out some of the rocks for fun. There is another group of grad students from University of Rhode Island and University of Texas Dallas who are covering this part of the mission. There are two main sampling methods: wax coring and dredging. I have described dredging in detail (see "The Mission and Instruments" post from the last cruise, 11/12/11) previously, so I won't talk much about that. Wax coring seems to be kind of a lame sampling method and doesn't really produce great samples, I think dredging will end up being the primary method. No dredging has occurred yet, we are waiting until we map the first area to identify good sites to dredge, but we did do a few wax cores when we had to pull up the deep-towed sonar for repairs two days ago. It's basically a cluster of small metal cylinders filled with wax that have a heavy metal weight on top and are attached to a wire extending from the ship. It's a pretty simple process, they basically just drop the thing overboard and let gravity slam it into the seafloor. Ideally little bits of rock will get stuck in the wax, which can then be removed and analyzed. To any non-geochemist, the samples are not impressive at all, they are literally tiny mm-sized bits of rock (or sediment if you're unlucky) that aren't much to look at unless you have a powerful microscope. They still can do chemical analyses of the tiny samples, so it is useful, but definitely not the best sampling method. Dredging may be imprecise, but at least you get lots of rock to look at. I'll post some pics once we actually get some dredged rocks. I think that covers the gist of what we are doing.

Science Background

The Mariana Trough is the southern portion of the Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc system, which is a subduction zone that stretches all the way up to Japan, and is the geologic feature along which the recent devastating earthquake/tsunami in northern Japan occurred. I don't know quite as much about the complex history of this area, but the basic situation is that the Pacific plate is subducting under the Phillipine Sea plate (a small plate sandwiched between the Pacific and Eurasian plates) in a roughly W-NW direction, creating a chain of arc volcanoes and a well developed backarc basin seafloor spreading system. For a more detailed but not-too-technical description of this area, check out the wikipedia page: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Izu-Bonin-Mariana_Arc. This area has been active for much longer than the Lau basin (~50 My instead of only 5-6 My for the Lau basin), and so has a longer and more complex history. One interesting thing here is that there has been two episodes of arc rifting, creating two backarc basins. The first episode separated the Palau-Kyushu Ridge on the west side of the system from the Izu-Bonin-Mariana arc, leaving behind the extinct Parece-Vela and Shikoku basins (see the map below). Then in the southern portion of the system, a more recent episode of arc rifting has formed the much smaller and still active Mariana Trough, which is the region that we are focused on. At the southern end of this trough, along the trench where the two plates converge, is the famous "Challenger Deep," the deepest part of the ocean in the world at almost 11,000 meters, although it is still possible that a slightly deeper trench may yet be found.

Map of the entire Izu-Bonin-Mariana (IBM) Arc system. We're looking at the southern Mariana Trough west of Guam and the region between Guam and the trench.

As you can see from the maps, the trench runs roughly N-S for most of its length, but along the southernmost portion of the system it makes a sharp bend and becomes almost E-W. The geometry of the subducting slab here is very complex and not entirely known. There appears to be a tear in the slab near the SW corner and while for the N-S portion of the system the slab is subducting in a W-NW direction under the basin, in the southernmost E-W portion, a small chunk of slab appears to be subducting in a more northerly direction. This piece of slab is plunging almost vertically down into the mantle, which is part of the explanation for why the Challenger Deep is so deep here. But, to make it more complex, while this chunk of slab is subducting toward the north, because it is still attached to the Pacific plate, it is also moving W-NW. This creates strike-slip motion along this E-W trending part of the trench, the Pacific plate is moving toward the W, and the Mariana Arc is moving toward the E as seafloor spreading continues in the Mariana Trough. There is another short wikipedia article on the Mariana Trough for those who want a little more info: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mariana_Trough. Friction along this boundary causes the overlying plate to rift apart, creating widening cracks that stretch from the trench to the backarc spreading center.

Bathymetry map of the Mariana Trough. We are mapping the area W and SW of Guam. Unfortunately the spreading center is not marked here, but it is ~1/2 way between the ridge that Guam and Saipan are on and the West Mariana Ridge. You can see in the north that the ridges have not yet split apart and are still a continuous volcanic arc. The dark blue crescent-shaped feature is the trench itself, you can see how it changes from ~N-S to ~E-W.

These rifts are the primary focus of our mapping and sampling, and have never been examined in much detail before. They also will be a major focus of my PhD work, the data we are collecting during this cruise will be the primary data set for most of my PhD. These rifts are called the Southeast Mariana Forearc Rifts (SEMFR), and there are two primary ones that we will look at. Unfortunately they are too small to be seen on the maps I've posted here, I'll try to get some more zoomed in maps later. Our survey will be divided into three legs, two of them along the two rifts, and a third along the spreading center N of these rifts. Less detailed mapping of this region has shown that there is active volcanism along parts of these rifts. As the crust is stretched and pulled apart, the mantle rises to fill the space and melts because of the reduced pressure, creating volcanic eruptions along these rifts, which is roughly similar to what happens along spreading centers. These rifts are unique because the slab is much shallower underneath them, starting at a few km depth near the trench and increasing to a few 100 km by the time you reach the spreading center. Normally, the first volcanism that occurs is along the volcanic arc (the row of circular red/yellow features that run along the west side of Guam and Saipan on the map above), where the slab is ~100+ km deep in the mantle. Between the arc and the trench (the forearc), the mantle typically does not melt, and even if it does, the crust is too thick for the melt to penetrate. But because of these rifts opening up in this region, the water-rich melt rising in the mantle has a window to get out onto the seafloor. Also, because the slab is so shallow and there is so much water being released from it, the mantle is relatively cool, so you don't get "normal" types of lavas that you would see along a spreading center or one of the arc volcanoes. I'll give some more details on this once we actually get some samples of this stuff, but one of the things I expect to see is serpentinite. Serpentinite is what is formed when the mantle (which is largely a rock called peridotite) reacts with water and incorporates it into the crystal structure (it is ~40% water by volume), and this can actually erupt onto the seafloor as serpentinite "mud". This requires relatively cool temperatures and lots of water, which is what you find in the shallow part of a subduction zone. Serpentinite is the state rock of California, and is normally found within the oceanic crust where water has reacted with the mantle. In California, it was scraped off onto the continent from the top of the subducting Farallon plate, it was not actually erupted onto the seafloor. It is very rare for it to be erupted onto the seafloor, so I am excited to see some samples of that. I think that covers the basic scientific background, I'll get into what we're doing and the instruments we're using in the next post. I tried to make this explanation accessible to non-geologists, but it is rather difficult, so if anything is confusing, let me know in a comment.

Saturday, December 24, 2011

Onboard R/V Thomas G. Thompson

The boat itself is significantly larger than the Kilo Moana, meaning that there is a lot more lab space, more deck space, and the rooms are larger. All of the science people have their own rooms, which is really nice. However, despite the fact that the room is almost three times the size of the Kilo Moana rooms, the beds are still the same tiny size. They could have easily added a foot or two of width to the beds and still had plenty of floor space, I'm not sure what they were thinking on that one. Beyond the larger size of the Thompson, the Kilo Moana is pretty much a nicer boat in every way. It is newer and cleaner, and the food was significantly better (although it's pretty hard to beat the food on the Kilo Moana, so that is not unexpected). We did have some surf and turf last night (steak/lobster), so there is good food onboard, but just not as consistently good so far, and generally lower quality. There are more public computers available and slightly faster internet, so that is a plus. There is a pretty decent lounge with a nice big TV and a bunch of movies, but the 70's fake leather seats and couches are not nearly as comfy as the huge soft black leather couches on the KM. The gym is also not quite as nice as the KM, they have a bench with some dumbbells, a decent non-electronic exercise bike, and a broken treadmill. I'm not sure why they thought free weights on a moving ship was a good idea, the KM had a pretty nice weight machine that seemed a lot more appropriate for a boat. But it's better than nothing, I've already used the gym twice. I think that covers the basics of the boat, let me know if you have any questions. I'll get into the scientific aspects of the cruise and my job on the next post...

Friday, December 2, 2011

The Final Post (until the next cruise...)

p.s. I'm still going to attempt to upload more photos to previous posts, although probably not as many as I would like given the painfully slow internet connection. Update: Done!! Check the older posts for new photos.

Friday, November 25, 2011

Update Time!!

A cool texture from the underside of a basalt sample. This texture forms on the underside of the roof of the lava flow from the lava dripping when the molten material drains out quickly.

A cool texture from the underside of a basalt sample. This texture forms on the underside of the roof of the lava flow from the lava dripping when the molten material drains out quickly. I know I had said in this post that we hadn't found sulfides, but we finally did find some in a later dredge. They're hard to see in this pic but the darker gray stuff toward the interior is Galena (lead sulfide), and there is a tiny amount of copper and zinc sulfide in some of the samples. It actually looks cooler with a hand lens when you can see all of the individual crystals.

I know I had said in this post that we hadn't found sulfides, but we finally did find some in a later dredge. They're hard to see in this pic but the darker gray stuff toward the interior is Galena (lead sulfide), and there is a tiny amount of copper and zinc sulfide in some of the samples. It actually looks cooler with a hand lens when you can see all of the individual crystals.Last night, I spent some time out on the upper deck by the bridge listening to some Bonobo (perfect star-watching music) and enjoying some fresh air. There was a beautiful view of the stars and it was refreshing to feel the wind whipping against me, I think I’m going to do that just about every night for the rest of the cruise. I saw a couple shooting stars and even a few flashes of lightning way off in the distance. But, as with my experience on the Langseth previously, the star-viewing is still not as good as I’ve seen out in the mountains of California. Even though there are only a few lights on the ship, it is enough to spoil what should be a perfect view of the night sky. I’ll try to get in at least one more update before the end of the cruise, but that’s all for now…

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Update after a week

Sulfur!!! The ones with the ripples are from the top of the molten sulfur lake, the large ones on top have some nice crystals, and the tiny grayish ones on bottom are the spherules

Monday, November 14, 2011

Environmental Impact

The Operation

1) Place two transponders on the seafloor in the vicinity of a known water column anomaly. These transponders tell the ship where the AUV is and also tells the AUV where it is, so the data can be properly located on a map. The ship uses GPS to determine its position, but GPS does not work under the ocean, so the transponders are the only way for the AUV to know where it is located and survey the desired area. This process takes ~6 hours.

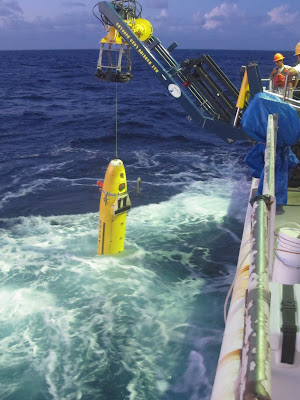

2) Deploy the AUV. There is a special launching structure that was bolted to the rear deck of the ship that lifts the AUV over the edge and drops it in the water. Deploying takes 30 min to an hour if all goes smoothly.

3) AUV mapping. The AUV then goes down to the survey area and maps the area on its own, then returns to the surface and sends the boat a signal to let us know to pick it up. The AUV mapping takes ~6-12+ hours depending on whether it stays down as long as it's supposed to.

4) Place next two transponders. Ideally, while the AUV is surveying the first area we will place transponders at the next area so it is all ready to go once the AUV gets to the surface.

5) Camera Tow. Ideally, we should have the data from the first AUV survey and then would tow the camera over this same area to get a better idea of the materials that are in the survey area. This step can be interchanged with the next step, dredging, if the AUV map is not quite ready.

6) Dredging. Hopefully, we have seen some hydrothermal chimneys in the AUV data and confirmed their existence with the camera tows. Then we dredge the area to collect some samples. While lava rocks are fine for the geochemists and are useful to tell us about the nature of the area, the Nautilus people are by far most interested in hydrothermally-derived rocks that contain economically valuable metals. We have not recovered any of these rocks from the first four dredges, but we undoubtedly will once we can actually target the dredges at actual known hydrothermal vent sites. The first four dredges have been mostly “blind” since we have not had the AUV data to help us know where to dredge. Hopefully, for the fifth dredge and beyond, we will have better luck.

While the above procedure is the ideal order of operations, it still has not happened according to plan once. We have had a number of issues, including the winch being wound up improperly, the AUV having difficulty contacting the transponders and aborting as soon as it got in the water, and the line used to retrieve the AUV getting caught in the propeller. There have been some technical difficulties with the TowCam and the AUV as well, but it seems that we have pretty much gotten those ironed out. One problem with the schedule being so unpredictable is that it screws up everyone’s sleep schedules, since we can’t really rely on things happening when they are supposed to. We have all had some very long days because of this unpredictability, but hopefully in the future we will be able to get on a somewhat regular schedule.

Post rock-sawing photo. The sawing was very messy for most of the cruise, and then we found out that it was because the blade was spinning the wrong way and blasting all of the water and rock bits up at us instead of down. Probably should have figured that one out sooner.

The First Few Days

The Boat and the People

The research ship we are using for this cruise is the R/V Kilo Moana, which is associated with my school, UH Manoa, although I think all

I had heard from multiple people beforehand that the food was delicious onboard, and it has most definitely lived up to that reputation. There is fresh salad available with a large variety of veggies for lunch and dinner, although I imagine that will not last the entire cruise. For breakfast, there is always eggs, bacon, sausage, usually some type of potato, yogurt, fruit, and then things like French toast or pancakes, all of it is pretty awesome. Lunch is pretty variable and there is always more than one option for a main dish if you don’t like something they are serving. The highlights so far have been bbq tri-tip and prime rib, which were amazing, and it’s only the first week. On top of the delicious meals, there is a never ending supply of snacks, including popcorn, nuts, doritos, ice cream, candy, chocolate, various kinds of cereal, and there are always fresh desserts made for lunch and dinner. In general, I eat much better on the ship than I do at home, so absolutely no complaints.

The People

There are 4 main groups of people on the boat: the crew, the Nautilus group, the Geomar group, a group from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachussetts (WHOI), and the miscellaneous scientists who are mostly from UH Manoa. There is also an onboard paramedic and an observer from

Drinkin beers with the Nautilus folks (and Regan) in Apia. The beer towers are pretty awesome, they have a cylinder that attaches to the lid and holds ice to keep the beer cold. They hold ~10 beers and cost about $20 US, not a bad deal :)

Saturday, November 12, 2011

The Mission and Instruments

AUV Mapping

AUV stands for autonomous underwater vehicle. Autonomous means that it is not manned and is not remotely controlled (which would be called a

The AUV on the dock, before being loaded onto the ship.

Camera Tows

Another method of studying these vents is using a camera that is mounted inside a metal frame and towed from a cable attached to the ship, cleverly named the TowCam. The camera is programmed to take photos every few seconds, giving us images of the seafloor which can be correlated with the mapping from the AUV to actually see what type of material the AUV is mapping.

Dredging

This is actually a very old technique for collecting seafloor samples, which hasn’t really changed much over the last ~50 years or so. The dredge is basically a rectangular metal frame with teeth around the outside attached to a chain bag. It is attached to the ship with a long cable and basically just dragged along the seafloor to rip up and collect rock samples. It’s probably the most crude and primitive sampling technique, but it has the advantage of typically giving us lots of rocks, sometimes more than we really need. One problem with it is that you can’t know exactly where the sample came from, but it gives you a general idea of the composition of rocks in the dredging area. This is the part of the cruise that I am involved with. Regan and I are assisting Ken Rubin, one of the geochemists from UH, in collecting and analyzing the samples. We also help with deploying and retrieving the dredge from the back deck of the ship, so we get to do some work out on the deck as well.

Since this is the part I’m involved in, I can give some more details on what we do with the samples after dredging. We first sort through and divide up the rocks into different types, so far we have only found two types: boninites (a gray to black lava rock that looks very similar to basalt), and rhyolite pumice (very light gray volcanic rock with an extremely large number of gas bubbles, making it very light weight so that it actually can float in water). Then, the geochemist will pick ~5 samples that seem to be the best for further analysis. We set those aside, give them numbers and do a brief description of them for the logs. Then, we try to chip the fresh glass off of the rocks, which is typically the outer part of the rock that cooled quickly and therefore has very few crystals in it. These glass chips are cleaned and saved for a microprobe analysis, which is not something that I know a whole lot about since I am not a geochemist. Then we cut the rock on a rock saw to see a fresh interior surface, since the outside of the rock is often covered in a manganese coating. Further cutting is done to basically produce a ~domino-sized piece that will be used to make a thin section, so that the rock can be viewed under a microscope and more precisely identified. Some chunks are saved to be crushed for a whole rock chemical composition analysis and so we can date the rocks once they are brought back to the lab at UH. I won’t be involved in any of the detailed chemical analyses, which I am perfectly happy with. I prefer to work at much larger scales, and geochemistry is probably my least favorite branch of geology. I’m glad there are people who enjoy doing it though, because it is extremely important for understanding things like the melting history of the rock, the composition of the mantle source that it came from, and the processes involved in creating the rock, among other things. Eventually, we will see samples from the hydrothermal vents that will get the Nautilus people excited, but for now we have only seen volcanic rocks.

By request, some more details on what geochemistry tells us and why it is important. (Sorry mom, I think your comment may have been deleted when I edited this post to add a picture and another section.) This is a very complex topic, but I'll try to give some examples of things that rocks can tell us. At a basic level, the chemistry tells us whether it's an igneous rock (solidified magma, either on the surface (volcanic) or within the crust (plutonic)), a sedimentary rock, or a metamorphic rock, but it gets MUCH more detailed than that. The rocks basically tell a story about the history of where they formed, what processes formed them, and what they have experienced since they formed. In igneous rocks, the composition and texture of the rock tell us whether the rock formed at a spreading center, an arc volcano, a stratovolcano like Mt. St. Helens, or in a huge frozen magma chamber like the granitic rocks of the Sierras. If there is a high water content, it usually means that the rock formed in a subduction zone, where the water from the subducting slab is added to the mantle. If there are lots of crystals, that means it sat around in a magma chamber within the crust for a long period of time before being erupted. If it is all crystals, it is likely a plutonic rock which cooled entirely within the crust and was never erupted onto the surface. If it has no crystals at all, that means it cooled very quickly after being erupted and did not spend much time in a magma chamber (the classic example being obsidian). If it has lots of vesicles (bubbles), that means that there was a lot of gas within the magma, and if there are very few bubbles it means either the gas escaped or there was not much gas in the magma to begin with. Certain trace elements can indicate whether a rock formed from melted sediment, continental crust, oceanic crust, or normal mantle, and whether there was some influence from a different process, like subduction or maybe a nearby hot spot. Ratios of radioactive isotopes typically don't change during the melting process and give you a more direct idea of the local composition of the mantle, which can help distinguish rocks that otherwise may be very similar. Isotopes are also used to date the rocks. In my thesis work, I used the ratio of two lead isotopes to determine how the influence of the subducting slab changed along the spreading centers that I was studying, which in turn gave insight into the structure of the mantle below and how the water-rich melt is distributed in the mantle. Metamorphic rocks were originally sedimentary or volcanic, but have been exposed to heat and/or pressure, causing them to change composition and texture, but not enough to melt them entirely. When you see a certain mineral in a metamorphic rock, it not only tells you about the composition of the original rock, but also how much pressure and heat that the rock was exposed to. Some minerals only form during weathering processes or when the rock is exposed to water, so they can tell you how long the rock has been exposed to the elements and what has happened to it since being exposed. In sedimentary rocks, which I probably know the least about, the chemistry tells you mostly about the composition of the rock that it was derived from and what the rock has been exposed to after being formed. That's a very basic introduction, let me know if there are more specific questions, although there is only so much I can answer in a blog.

Sonar Mapping

Friday, November 11, 2011

Science Background

The Study Area:

We are going to be sailing around the ocean a few hundred km south of Samoa, and ~500 km east of Fiji. We are in the Lau basin, which is the same geologic feature that we studied during the last cruise in 2009, but we are ~500 km N-NE of the previous study area. The Lau basin is a backarc basin associated with the Tonga subduction zone. Very briefly, a subduction zone occurs where two tectonic plates converge, in this case two oceanic plates. One plate, in this case the Pacific plate, sinks down under the other and penetrates deep into the mantle. This is occuring around nearly the entire rim of the Pacific plate, creating what is known as the "Ring of Fire," as well as various other places around the world. Subduction zones are the locations of the largest earthquakes and volcanic eruptions around the world, e.g. the recent Japan quake, the large quake in Chile a few years ago, and the infamous 2004 tsunami in Sumatra, so they are a very important geologic setting to learn about. In order to understand what we will be looking at, I'll give a brief introduction to some of the major processes along subduction zones before I get into what we'll be doing:\

1) Earthquakes (large and small, deep and shallow) occur along the interface where the two plates come together and grind past each other. Large ones occur when the plates "stick" and lock together for a long time, building pressure until it is all released in one large event. These quakes often cause tsunamis as well. Smaller quakes occur when the plates move a little bit at a time and don't get the chance to build up a lot of energy. Earthquakes also occur due to the plate bending and cracking as it sinks down into the mantle, but these are typically smaller than those that occur where the two plates directly rub against each other.

2) Volcanoes: the subducting plate (called the "slab") is saturated with water and as it descends into the mantle this water is slowly squeezed out of the sediments and rock and released into the overlying mantle. Also, at ~100-200 km depth, minerals that have water bound in their crystal structure undergo a chemical reaction that releases this water, creating a sudden influx of water at these depths. When water enters the mantle, it lowers the mantle melting temperature and decreases it's viscosity by a huge factor, causing melt to buoyantly rise and penetrate into the overlying plate above. This creates a linear chain of volcanoes on the seafloor, called the arc volcanic front, or the arc for short. These volcanoes can grow to become islands that break the sea surface or they may just continue erupting under water. When the overlying plate is a continental plate, you get volcanic chains such as the Andes Mountains in South America or the Cascade range along the west coast of North America, where Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Rainier, Shasta, Lassen, etc. are located. There are other materials and chemicals released from the slab as it subducts, but water is by far the most important in creating this massive amount of volcanic activity.

3) Backarc extension: This part is a little more complex and not fully understood, but this is the part of the system that we are currently looking at and that both my Master's and PhD work focus on. While convergence is the dominant overall plate motion in a subduction zone, the region behind the arc, away from the trench where the two plates come together, can actually undergo extension. The first thing to help understand how extension can occur in a convergent setting is to realize that the slab is not being shoved down into the mantle, but rather sinking and falling away from the overlying plate. The trench where the two plates come together actually migrates away from the arc in a process called trench rollback, although it should be noted that this does not occur in every subduction zone. Because the two plates are coupled together at their interface, the slab actually pulls the overlying plate with it, causing the overlying plate to be stretched. This stretching causes rifting near the volcanic arc, where the crust is thick and weak, which over time matures and concentrates along a single spreading center, similar to “normal” spreading centers along the mid-ocean ridge system, where extension rather than convergence is the dominant tectonic process. As the plate is pulled apart, the mantle beneath rises to fill the space and actually melts because of the decrease in pressure, causing volcanism along the spreading centers and new oceanic crust to form. So in a global sense, crust is continually being destroyed at subduction zones and created at spreading centers. These two processes are balanced, otherwise the earth would be growing or shrinking, which we know is not the case. One amazing fact is that the entire process of plate tectonics is driven by the fact that the solid plate is ~0.5% denser than the mantle below. Without this density difference, the plates would not sink into the mantle, subduction would not occur, new crust would not be created, and all of the land above sea level would simply slowly erode and shrink over time until we would all be living in a world entirely covered by water.

4) Hydrothermal Activity: The process that we will be focusing on during this cruise is hydrothermal activity. Hydrothermal vents can occur in any location with active volcanic activity where there is magma residing within the crust, in this case individual volcanoes and spreading centers. Water penetrates the crust through faults and cracks, and even through pore spaces in the sediments and rocks. When the water comes into contact with magma or hot rock, it is quickly heated, often to 4-5x the boiling point, and it is ejected through hydrothermal vents on the seafloor. On its way up through the crust, the water dissolves metals and various minerals out of the crust, which are then ejected at the seafloor vents. These metals and minerals precipitate out of the superheated water when it hits the cold seawater and are deposited on the seafloor around the vents. This is actually the original source of nearly all precious metals, such as gold, silver, platinum, copper, and zinc. These metals end up on land by being scraped off of the slab onto the overlying plate during subduction under a continent. All of the gold in the Sierras in California